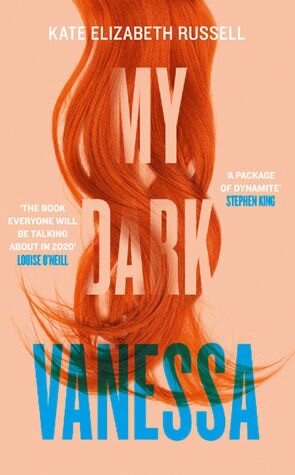

How and Why Abuse Happens Terrifies Us Now It’s Time to Talk About It

Kate Elizabeth Russell portrait by Dina Litovsky

I didn’t want to read this book, I would never have picked it for myself. That’s the trouble with a book club and a bestseller list.

While ‘My Dark Vanessa’ is not a book you can ‘enjoy’, there is no denying the brilliance of the writing. It takes a special author to hold you to their story with words that flow so easily through your mind, even while you desperately want to turn away. Compulsively readable, it is a fictional tale in which you have a rough idea of the destination you’re headed for but are gripped with the tension of how exactly you will get there.

Kate Elizabeth Russell wrote with an unflinching gaze at a subject matter most of us willingly avoid, and her skill demands that you stand beside her for the journey. I consumed the story in 24 hours.

It felt like jumping into the sea and knowing you can only hold your breath for so long. I was willing to be a witness but I didn’t want to be inside the book any longer than I had to, and my relief on the last page was physical.

The story of Vanessa and Strane itself while important and obviously central to the book was not for me the most troubling, haunting, or even the most important message in the book’s pages. There were several others.

How could this happen?

Where were her parents?

Why didn’t she leave?

And then later… Why doesn’t she want to tell, to bring him to justice and make him pay?

The idea of a romantic relationship is the basis of Vanessa’s understanding of her connection to Strane. From the beginning, he encourages the idea that he is doomed by his bad luck to fall for a girl who happens to be only 14. Why couldn’t he have a soulmate this lifetime in a woman the same age as he?

The reason this manipulation works so easily is that as a storyline, forbidden love is one of our favorites. The notion of us against them unifies people faster than any other commonality. Our books, movies, legends, and fairy-tales are all dripping with this narrative, making it an easy pathway into coercion. After all, when you are offered the very thing you most crave, it is hard to say no, and admit to yourself that perhaps all that glitters is not gold.

We use the language of love to mask many traumas.

The psychology of men like Strane relies on the narrative of being ‘in love’ and being a victim to that love and her power over him, which is essential for enabling him to continue to live and manage the normal world while being a predator with her. It is a dissociative split that is fundamental to acting in ways that we know are simply wrong. A rationalization which society is complicit in via movies, books, and other forms of storytelling repeatedly over-sexualizing the schoolgirl/young girl image. Portraying her to be a temptress, full of knowing and deliberate seduction of a weak and feeble, innocent man. A story echoed down since the time of Eve.

“He touched me first, said he wanted to kiss me, told me he loved me. Every first step was taken by him. I don’t feel forced, and I know I have the power to say no, but that isn’t the same as being in charge. But maybe he has to believe that. Maybe there’s a whole list of things he has to believe.”

The idea of having power as a young woman is intoxicating when you are part of a society that belittles you as ‘too young’ to have an opinion, ‘too young’ to have an impact on the world. ‘Too young’ to be responsible for decisions about your life and your body, but perhaps not too young to have sexual power over a man.

“I can’t lose the thing I’ve held onto for so long, you know?” My face twists up from the pain of pushing it out. “I just really need it to be a love story, you know? I really, really need it to be that.”

“I know,” she says.

“Because if it isn’t a love story, then what is it”?

The ugliest truth of the book for me is the reality that each person in her life failed her to some extent, and this is an all too palpable reflection of real life. Schools and other agencies fail to address sexual assault because we as a society still refuse to. If we were to address it head-on, that would mean each person having to accept that they can look back through their own histories and find experiences of inappropriate sexual attention, and possibly evidence of being the perpetrator of that attention.

The word ‘attention’ itself minimizes the long-lasting impact words and gestures, suggestions, and mind games can have on the young. Attention is what we accuse children of seeking.

Any institution in which there is a power hierarchy is ripe for abuse and manipulation. That means the people within them for countless reasons will, if they look, find themselves as part of the problem rather than the solution and that is incredibly painful and confronting to deal with. So painful that many refuse to see the evidence in front of them.

Gather any group of women together and ask them if anyone has had any experience of unwanted sexual attention, and each one will be able to recount something. Stories of a hand on a knee on a bus ride, an uncomfortable conversation with a teacher who invaded their space, an older man making uncomfortable comments about their appearance, memories of the flasher on the way home.

I remember when the statistics were 1 in 3 women would have experienced a sexual assault, and that was a long time ago. What strikes me now is how we define assault.

So often our minds are unreliable in a situation, frozen in shock by the actions of the other, the only reactions we can trust are those of the discomfort in our bodies. The tightening of the stomach, the crawling on our skin, the shiver down the spine, and hot and cold flashes as we struggle to make sense of the smiling or neutral face, that seems to say ‘What’s wrong? Nothing is happening?’ even while your body is sensing an immediate threat.

If my understanding is accurate then every woman has had an experience of some kind, but how can that be? How can this be perpetuated so consistently without consequence, without an uprising to ensure that abuse is stopped?

But there is the truth of the problem, without confronting our own experience, our own definitions of what is acceptable, then we cannot help or stand for anyone else.

Can we get comfortable enough to bring the subject of abuse into the light of our everyday lives? Can we talk about it with our partners, our children, and our colleagues? For that is what is needed to protect and fundamentally change a culture.

Some things are too painful to look at, so we don’t, but in not looking we are less able to make a change. So how do we create enough personal safety to feel secure enough to give voice to the darkness?

Personal autonomy and agency seem to be at the heart of this question. The power we have to choose what happens to us physically, mentally, and emotionally. The power to choose our story.

Raised also in the book were questions surrounding the ‘Me Too’ movement from the viewpoint of a survivor who doesn’t want to share, who doesn’t want the past to be made public.

Is one unintended aspect of the movement an unwitting retraumatization of survivors who are confronted by the stories of other women, a stark reflection of their own memories?

What would it mean to see your abuser outed publicly, and to see the faces of other women with whom you share an unspoken and unwilling bond?

Is shared truth enough to mean our experience does not belong solely to ourselves? Is there an obligation to share when that truth can be the evidence needed to stop a perpetrator from finding a new victim?

There seems to have been a moment in which we collectively understood the ridiculousness of blaming survivors for the actions of their abusers. We took control of our own grief and fear, our reactions to the truth that darkness is sometimes a very real and present reality, and that it hurts those we hold most dear.

We began to learn not to use shame against them in some bizarre way of protecting ourselves from the horror that in some people is lurking beneath the surface, hiding behind the faces of the trusted.

At what point did we turn from shaming survivors to using guilt against them? Creating the idea of it being selfish not to share, not to do their part to bring justice to the perpetrator, even when that offers no solace to them, and worse still manipulates, isolates, and hurts them once again.

‘I feel backed into a corner,’ I say. ‘like all of a sudden, not wanting to expose myself means I’m enabling rapists.’

There are many things to learn from this story, there are of course the backstories that would illuminate the how’s and why’s of what brought him to become a master manipulator, able to identify the vulnerable one in a group of children in his classroom. The backstory to better understand what made her so vulnerable and perhaps lessons to be learned of how to strengthen and protect her.

Important for me are the lessons about what we do next, what we do after the predator has struck.

How we can turn the unflinching gaze on ourselves, our rationalizations, and our mumbled apologies while we continue with our lives?

We are all survivors of a culture that has created a breeding ground for this narrative to exist. We are all complicit in not holding the eye of the survivors who do speak out, of not hearing their rallying cry for longer than the news cycle it comes to us on.

However, we all have the choice now, of how to use our agency and our voices. Whether that be to join our voice to the voices of many and call out our Strane’s, adding an echo to the reverberations of ‘Me Too’. Or whether that be in engaging in the uncomfortable conversations and raising the next generation to be stronger and more certain of themselves and what is unacceptable.

We each are on a journey to find and own our voices, but this is a journey made so much easier when we don’t have to travel alone.

“If there’s one thing you take away from this class, it should be that the world is made of endlessly intersecting stories, each one valid and true.”

________________________

Originally published in Books Are Our Superpower in March 2021